Music As Studio Art: An Interview With Morton Subotnick

The article below was originally published at the now-defunct Decoder Magazine on October 12th, 2017.

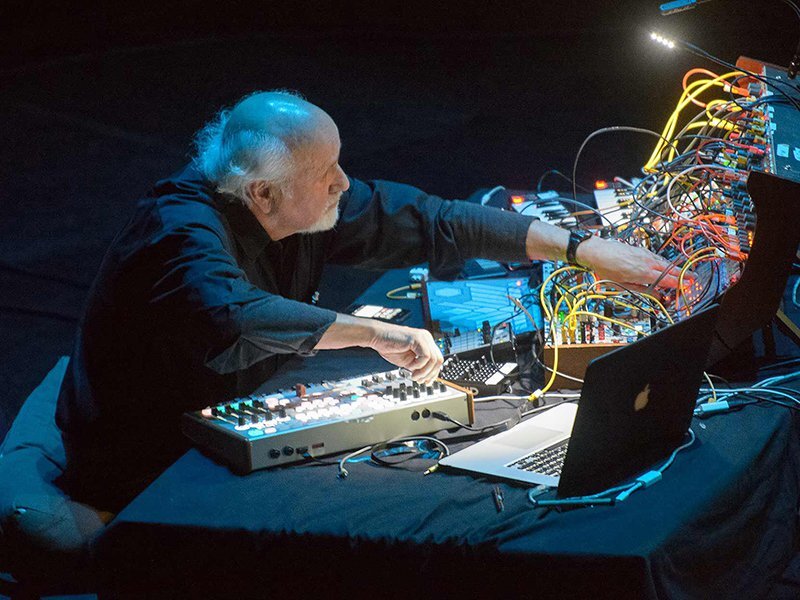

Morton Subotnick is one of the most significant figures in electronic music history. His seminal Silver Apples of the Moon emerged as the first fully electronic album ever recorded and has since been included in the National Recording Registry within the Library of Congress. To realize this work, Subotnick worked with Don Buchla to create the first modular synthesizer, now housed at the Smithsonian Museum.

Subotnick started the San Francisco Tape Music Center with composer Ramon Sender, an artistic scene that fostered minimal composers Terry Riley and Steve Reich, Deep Listening creator Pauline Oliveros, visual artist Tony Martin, percussionist William Maginnis, and many others.

Subotnick has taught at Mills College, held the position of Associate Dean at CalArts, and was the music director for the Actors Workshop as well as the Lincoln Center Repertory Company. In addition, Subotnick was an artist-in-residence at the Tisch School at NYU.

Throughout his career, Subotnick has composed for symphonic and electronic arrangements alike, but Silver Apples remains his most indelible work. This year, Subotnick celebrated its 50th anniversary by performing the work across a three-day run at Lincoln Center in New York City.

Tristan Kneschke: How did your parents foster your musical interests as a child?

Morton Subotnick: I developed a bronchial condition when I was about six years old. The doctor said I should maybe play a wind instrument to help my lungs, so I chose an instrument I’d seen in a Glenn Miller movie. I described the instrument to my parents, that it had a slide that moved back and forth, but they didn’t know what it was called. My mother brought home a book of orchestral instruments. It had no pictures in it, just names and descriptions of instruments. I ended up picking the clarinet.

The instrument came but it wasn’t anything like what I’d chosen. When my mother asked if it was the right instrument, I still told her it was. I couldn’t even put the instrument together. That was the beginning of my musical career. My parents didn’t know I’d made a mistake until they read an interview in the paper when I was about 30 years old.

Was music always playing in your house?

No, although my father was very artistic and would paint on the weekends. He played violin as a kid, but I never saw him play as an adult. His parents had talked him out of continuing because they thought it was a sissy thing to do. Then when he wanted to be a painter, they told him artists didn’t make a living, so they talked him out of that too, even though he’d gotten some scholarship. Other than that, we had a piano in the house, which I think my mother tried to learn. She took lessons at one point.

My mother got me a clarinet teacher who taught lessons at the house. She was very concerned if I didn’t practice because she thought it would reflect poorly on the family. My lessons were in the dining room near the kitchen which had a swinging door on it. She would stand behind the door listening to the lesson.

One day, she hears this squonk from the clarinet and swings the doors open, scaring both the teacher and I. She starts apologizing to the teacher, saying, “He’s never done that before.” The teacher said, “It wasn’t your son. It was me. Your son actually plays better than I do at this point. I think he needs a better teacher.”

So I was pretty precocious on the clarinet. I played my first concerto with a symphony orchestra when I was about 16. I could basically play anything you put in front of me, though I did practice hard. I’ve always been very organized about how I use my time, even as a little kid. Come to think of it, maybe I wasn’t so precocious. Maybe I was just working harder than other people.

Your Juilliard audition didn’t go as planned. What happened?

I was about 16 when I made arrangements to audition there with the main clarinet teacher. But they weren’t teaching in the summer. He was in Pennsylvania at his summer home, but I’ve never had any sense of direction. I never have. Somehow I borrowed my dad’s car and drove from Sheepshead Bay in New York to Pennsylvania and found his house. To this day I don’t know how I did it. There was no GPS back then.

The last thing I played was excerpts from Mozart’s Clarinet Concerto. He gave me a couple of little pointers, and then said, “I’d be glad to teach you.” I said my parents didn’t have any money. He said, “Oh, that’s okay. We’ll give you a scholarship. I’ll see you a year from now.” Then he said, “My time is very valuable, and I charge $10 an hour. You’ve been here 45 minutes, so you owe me $7.50.” I walked out feeling so embarrassed that I didn’t know you were supposed to pay for an audition.

Driving back, I got halfway through the Lincoln Tunnel when the car stalled. I had all of New York screaming at me. I felt like I wanted to be invisible. It was just terrible.

My cousin and father picked me up. I was in the backseat feeling like an infant, just totally out of it. Then anger started to take the place of everything else. I thought, “It may be that you’re supposed to pay for an audition, but it’s wrong, and I’m not going to a school where they collect $10 from kids who drive across the country just to audition,” and I made my decision not to go to Juilliard. Instead, I went to USC, which was a game changer. It offered a trajectory that otherwise never would’ve happened.

How were you approaching music back then? At that point, were your instruments just simple oscillators, wave generators, and tape editors?

By 1959, commercial use of the transistor became news. The idea was that electronics, which were very expensive in those days, would now be dirt cheap. At the same time, I was reading early Marshall McLuhan lectures from what would later become Understanding Media. I can’t tell you how mind-blowing that was. McLuhan had the notion that society was going to change radically through new media, and music was going to be one of the catalysts. I became aware I was alive at a moment where music was going to undergo a similar transformation that language underwent with the advent of the printing press.

I thought I was a really good clarinetist, but there were a lot of people who were, and that I was a good composer, but I’d never be Beethoven. I decided that if I had the aptitude to contribute to this moment, I would give up the clarinet. This is at a time when most of the population, including musicians, were scared of these new directions. I began to develop the idea of music as a studio art like painting, where you wouldn’t need musicians or learn notation. You just make music in your studio.

The bigger pieces I made were basically cutting and pasting. We didn’t have mixers, so you had to splice crossfades without much room for manipulation. You also had tape recorders that played at different speeds, even when you didn’t want them to. I had this little stop-start thing that would allow me to open and close a gate. If I had a sample going on a long tape or a loop, I could pause it, but I couldn’t control the envelope movement. I could give it a tempo only by pushing a button and then make a loop of it. But I never thought to use it for regular things anyway.

A lot of key music figures came out of the Tape Music Center. Can you paint a picture of what the scene was like? How much did you collaborate with each other?

Ramon had a little studio with a real, honest-to-god, Hewlett-Packard oscillator, and I had a garage full of automobile parts and an old broken-down piano that I used to make sound. I was essentially creating music with crap. He called me one day and said, “Why don’t we pool our two studios? We’ll have electronics and all your stuff and a couple of tape recorders.” That’s how the San Francisco Tape Music Center got started.

At first it was just Ramon and I. When we needed money for equipment, we had to become a nonprofit. The place was this big Victorian house that was going to be torn down. We rented out the rooms upstairs to artists and then gave concerts once a month to collect money to have some income. We ended up getting another place and combined with experimental dancer Anna Halprin and the KPFA radio station. That became the main center that everybody knows.

The moment was just incredibly ripe. I decided to open it up and really treat it like a place where any composer could come and work. Composers from Russia would even come into San Francisco. That was very rare for the time.

It became a meeting place, a center for all kinds of creativity. We let other people use the auditorium when we weren’t using it, so there were all sorts of concerts going on. I didn’t how half the people. Laurie Spiegel told me years ago that was her introduction, but I’d never even met her.

You found Don Buchla simply by placing an ad in the newspaper. In working with him, was he designing something to your specs or did you get more involved on the electronics side?

I talked him through what I was after, and he would practically design as we were sitting there. He was pretty advanced, very brilliant. I gave him the musical functions, and because I was reading a lot, I began to understand the point of transistors, diodes, and resistors. I would come up with these Rube Goldberg versions of how I thought things would work, and he would translate the functions into how they would actually work. I was interested in making the sound, but also how you tell the machine to make the sound. It was also important that there was no black-and-white keyboard. He worked with all of that.

We tried all kinds of trigger devices, including rotary dials. I knew about automatic stepping, and Don said, “Well, that’s a sequencer. There’s a design for that.” He also came up with the idea of separating control voltage physically from audio. The amount of control voltage I wanted to flexibly use couldn’t be done cheaply with audio. The audio cable itself requires grounding, which is not necessary for low voltage. That decision alone allowed me to stack banana cords, which if he did that with audio, you’d have to make active modules, which are not as modular. That was one of the real breakthroughs.

When the Tape Music Center received a Rockefeller Grant in 1966, it had to relocate to a larger host institution, becoming the Mills Tape Music Center at Mills College. You left for New York with a new Buchla modular to work on Silver Apples of the Moon. Soon, artists and musicians would regularly congregate at your Bleecker Street studio to watch you create bizarre sounds that had never been heard before. Do you have any anecdotes about prominent figures that would drop by?

I worked all through the night because I had to get my kids off to school in the morning. The door didn’t lock downstairs, and we had no lock on the door upstairs where the studio was, so people would just come in. I didn’t pay much attention. Ultra Violet from Andy Warhol’s group was the only one I met. And below us was Bleecker Street Cinema, where one time the guy came up and told me I was too loud and I had to shut down.

You weren’t worried about not having locks? At that time, New York City was extremely dangerous.

I know, but I never had anything stolen. We had the case of a video camera that looked at you with a sign that read, “You are being watched,” but there was no tape in it.

That’s crazy.

Yeah, the place had someone in it almost all the time. When people came over, I would give them a task, like clean the bathroom once a week or something. I never thought about giving things away for nothing, but I would also never charge them money. Serge Tcherepnin [who later would create the Serge synthesizer] came to me one day and said, “I’d like to learn, could I make things for you?” And I said, “Sure.” So he and his girlfriend at the time, Maryanne Amacher, moved in. I had a storage room that was quite large, but had no windows, where they lived for a few months. Serge would later come with me when I went to help start CalArts. His full-time job as a faculty member was to develop a modular synthesizer, which became the Serge Modular.

How did you construct Silver Apples? Did you record takes to tape and then splice them together?

It was done on a huge array of Buchla equipment and two two-track tape recorders. One recorded and played back, and the other only played back. The whole idea was to perform and record the studio. I played with “gooshy” pitches [of long sequences] and discrete pitches – short bursts of sound. I would take the gooshy pitches and create a patch, which might involve two-thirds of the equipment, and perform it to get some ideas. They wouldn’t be pitches or anything, but diagrams of timings and ideas to give me something to look at. I would record gooshy pitch things over a period of three to five weeks until I had maybe 40 minutes of performances.

Then I would work on the discrete pitch stuff on a different patch. I’d record the discrete stuff by itself, then playback the gooshy stuff and perform against it. So I’d have three tapes: a mixture of the two and each one individually. I gradually put it together over the next 13 months.

Were The Wild Bull and Touch created in a similar manner?

Everything was created that way prior to Until Spring. During Touch [1969], Buchla made me an envelope follower for using the amplitude of my voice as a controller. I can’t find the existence of one before that, but I didn’t actually use it in Touch. I was just experimenting with it. Sidewinder [1971] was primarily completed with my voice, where I would get a tape of the control voltage, and use it to control while I used my fingers. I was like an octopus at that point. I had lots of different control things.

In Sidewinder, I developed a technique using my tongue to make like a SMPTE pulse track that allowed me to lock things together. So the overdubbing now could be synchronized, because the next patch could be pulsed, running a sequencer off of it. By the time I got to Until Spring [1976], I used it exclusively, and then A Sky of Cloudless Sulphur [1980] was just a really sophisticated use of it because by then I had an eight-track tape recorder. It was a pretty intense use of a kind of automation. There was no more splicing by then. It was really overlapping because I had about three tape recorders by then. That was quite different from Silver Apples.

Recently, you performed “Silver Apples of the Moon Revisited” for three nights at Lincoln Center. Did you start with the original patch and improvise from there?

The whole idea of Silver Apples was not to have a performable piece. It was all done in post-production. I would’ve had so many things onstage, and have five performers to play it, even if I could remember the patch. I could only automate part of it.

In the performances I sent a pulse to the Buchla. I controlled and duplicated oscillators in Ableton and used samples from the original. I sent stuff through these bumping and granular gates, so things flew around the room [in quadraphonic sound] or mixed with the original. People came to hear Silver Apples, so I used a lot of the original stuff but added to it. It wasn’t just played through. It was a kind of remix, but you could recognize a lot of the original stuff.

You’re duplicating Buchla oscillators in Ableton that are then sent back to the modular?

Yes, those were real oscillators fed back to the Buchla in real time. Then I had sampled stuff that was performed with those oscillators. The issue with the Buchla was always how much equipment you needed. You have to be an octopus to play them.

Ableton’s a great application to use with it because it’s pretty neutral. I could just take an oscillator and have it go to the first input on the interface and then duplicate that all with input one. You can just make a whole bunch of tracks.

If you have five tracks just from input one, you’ve got five oscillators. You’ve got one oscillator going to five places. Now I can take the oscillator and send it to a gate, a voltage-controlled amplifier. Number one goes to voltage-controlled amplifier one, and that’s being controlled by changing overall amplitude, and the frequency is shifted down an octave and it’s got a modulation plugin that enables it. So it comes back in a different form and you can play it as a quiet thing moving around the room.

That same oscillator on number two goes into one that has a pulse on it or a beat of some sort. The only thing in common is that when I change the pitch, all of them change at the same time, but it’s not the same pitch. I can make it a major third above the original.

So two or three oscillators can give you a huge palette of real oscillators. Then they’re multiplied in Ableton, modified if I need to, and sent back. Then if I send a sample of some part of Silver Apples into that same gate that’s moving around the room with an oscillator, I can still bring the original in. It just makes the palette huge.

So when you’re sending signals from Ableton to the Buchla, that’s not MIDI information anymore, correct? You’re sending it back as audio?

It goes back as audio. I can send MIDI information into the Buchla but I don’t send MIDI information from the Buchla back into Ableton. I can control things either with the Buchla, with knobs and so forth, or with MIDI, so it frees up hands and fingers.

I’ll have a sample of one of my music pulses that I turn into MIDI in Ableton, and I can send that out as a pulse in place of a pulse generator in the Buchla, so everything can be synched by that. It’s the music you’re going to hear, but I’ve taken it out of context and turned it into pulsing. Tempo basically turns the audio into a MIDI file and then sends it out as a pulse.

It then becomes the cloth for one part of the piece. You heard this in different parts with the voice in [the second Lincoln Center piece] Crowds of Power. As [vocalist and Subotnick’s wife Joan La Barbara] sang, you heard this pulsing with her voice an octave above, moving around the room. That was being run by an audio file I performed earlier, syncing everything, so when I brought it up at the end, it was in total synch with the pulsing of her voice.

It’s a really neat thing, but it’s taken me seven years of work to figure out. Maybe someone else could do it a lot faster.

You’ve said the new work, Crowds and Power, is a 21st Century 19th Century music tone poem, a musical version of Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra. Can you elaborate on that?

Crowds and Power is around 50 minutes long, and it’s got a lot of stuff in it, including a performer onstage [Subotnick’s wife, singer Joan La Barbara] and lighting. I started back in the ‘80s working towards this tone poem thing.

I believe live performance should have a visual element. I began to add the live element right from the beginning by working with other artists.

We think in language, and that’s part of the problem with a musical instrument. We spend all this time talking, but you don’t really get it until you really absorb what’s missed in studio art.

Sometimes a sentence can have two meanings. The same words might not mean the same thing. That meaningfulness is the essence of musical communication. You can talk and think in tones, and each of those gives you a limited array of meaningfulness. That’s the range of what you get in a tone poem. You understand it from the intonation of the music as it goes. So in Crowds and Power, there are no real words anywhere. There is no absolute narrative, but you get it from the meaningfulness of the communication, not the meaning of the communication, and the musicality, all those elements of shapes and image. Sometimes you get an image which is a real image, but they’re mixed without the narrative. They’re mixed in nonverbal communication.

Morton Subotnick’s memoirs are forthcoming from MIT Press.